Nick Shaxson ■ Tax Justice Research Bulletin 1(3)

By Alex Cobham, TJN’s Director of Research

March 2015. Welcome to the third Tax Justice Research Bulletin, a monthly series dedicated to tracking the latest developments in policy-relevant research on national and international tax.

This issue looks at new papers on the responsibilities of tax professionals in respect of abusive tax behaviour and corruption; and on the parallels between the 2008 financial crisis and that of 1974. The Spotlight section considers contrasting views on tax and freedom.

This month’s backing track, by Creedence Clearwater Revival, was suggested by Christian Hallum. (if it’s not available in your area, try this.)

Responsibilities of tax professionals

“Why is abusive tax avoidance the prerogative of wealthy individuals and large corporations? Primarily because a very high level of technical expertise is required to establish and manage an effective tax avoidance strategy, and that expertise does not come cheap. A large and multifaceted industry of professionals – including lawyers, accountants, finance specialists, bankers and offshore service experts – thrive on creating ‘tax benefits’ for those who can afford their services.

…

Our primary aim is to argue that tax professionals […] have specific responsibilities to help reduce the incidence of abusive tax avoidance and remedy its negative consequences.”

This is the basis for a new paper, ‘Abusive tax avoidance and institutional corruption: The responsibilities of tax professionals’, by Gillian Brock and Hamish Russell. (Brock is one of the world’s foremost cosmopolitan philosophers, and an earlier version of this paper won the Amartya Sen prize.) The paper builds on Lawrence Lessig’s work on institutional corruption, defined as the illegitimate weakening of an institution, and especially of public trust in it.

The paper highlights the role of various tax professionals in corrupting fiscal institutions, creates a framework for assigning responsibilities for tackling the problems, and applies it to three groups in particular: accountants (the Big 4 firms), lawyers and financial advisers.

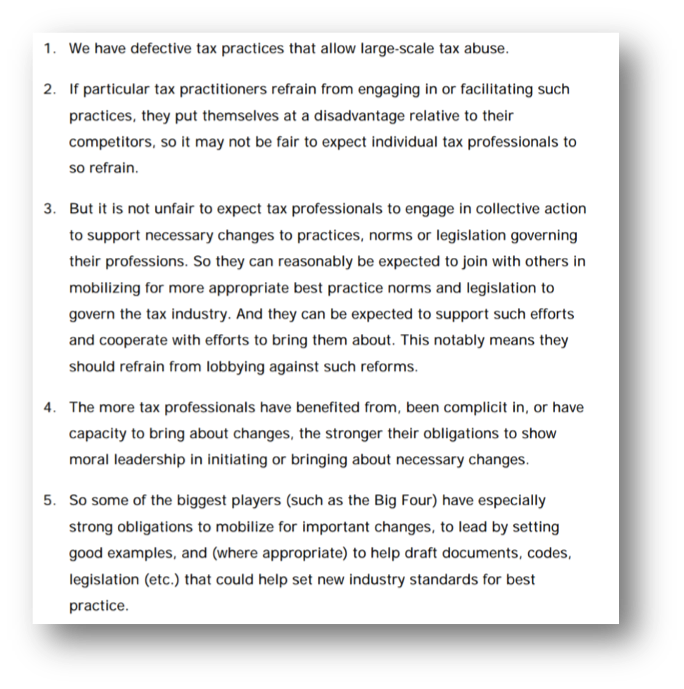

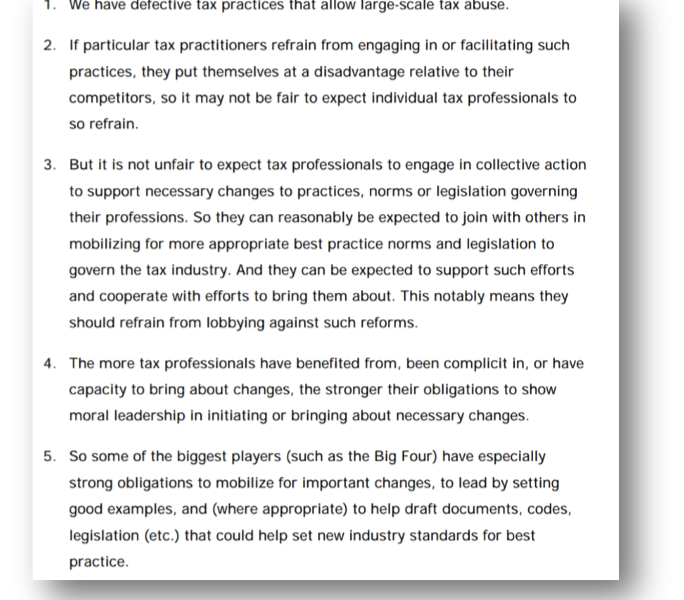

In each case, Brock and Russell explore the causal contribution of each group of professionals, the extent to which they benefit, and their capacity to bring about remedy. The figure above here outlines the structure of the argument, for the case of Big 4 firms, and points to the type of collective action that might be fair to expect, as a moral response.

Some may question the policy recommendations: if part of the weakness of tax rules results from lobbying activities of tax professionals, is it reasonable to expect the same professionals to act from their position of power to reduce the opportunities that exist?

But the paper provides a logical clarity to what many will already feel: that (some/too many) tax professionals have sometimes, or for too long, benefited from exploiting the weakness of tax systems; and that ultimately any important steps towards progress will need to be taken with the acquiescence, if not the active leadership, of at least some professional groups.

Spotlight: tax and freedom

Tax Freedom Day began in the late 1940s in the United States, as a political marking of the day when the nation has in theory earned sufficient income to pay the total tax for the year. In other words, the same proportion of the year has passed, as the expected proportion of taxes to GDP. Tax Freedom Day is now calculated and publicised, generally by quite right-wing organisations that seek to paint tax as a threat to democracy, in a handful of other countries.

A basic critique of TFD can be constructed on the basis that lumping the whole nation’s taxes together obscures more than it reveals. You could tell a very different political story, for example, by comparing the ‘tax freedom’ day of a median-income employee of a given company, with the ‘tax freedom’ day for the company itself.

But perhaps the more substantial criticism revolves around how or whether tax and freedom have any relationship with each other. The well-known slogan ‘no taxation without representation’ suggests that there may be something to this.

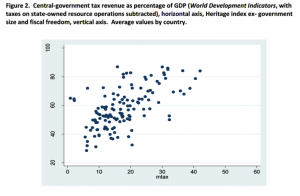

It turns out that there is hard evidence for this too: there seems to be a relationship between the proportion of public expenditure funded by tax, and the strength of democracy. In fact, this is one of the more well-established results about aggregate taxation, in fact: the notable references here are Ross, 2004; and (even more clearly) Prichard et al, 2014, using the new ICTD Government Revenue Dataset.

Putting it bluntly, political freedom (meaning in this case the freedom facilitated by effective political representation) seems to rise, as reliance on tax increases.

But what of economic freedom?

A new paper from James Mahon sets out to examine just this question, using the ‘freedom’ measures created by the range of relatively right-wing organisations that have tended to support tax freedom day – notably the Fraser Institute, and also the Heritage Foundation. As with the democracy studies above, Mahon finds an important distinction between tax and spending. There is some evidence of a negative, or zero effect of higher spending on some measures of economic freedom. But for tax, the finding are clear:

“States that taxed more in the 1970s tended to broaden economic freedom in later decades; and after 1995, higher levels of taxation predict more economic freedom, on two different measures, in the following year…

[T]he need to expand tax revenues in order to pay down debt, tends to keep governments attentive to what pleases investors and inspires the compliance of taxpayers – whether or not these mount colourful demonstrations against the ‘tyranny’ of big government.”

The failures of international financial regulation: 1974 all over again

“[D]espite the dramatic changes which have occurred in the nature of global financial markets over the past forty years, the challenges to the regulatory and supervisory system first identified in the banking scandals of 1974 have persisted.”

I remember when reading Nick Shaxson’s ‘Treasure Islands: Tax havens and the men who stole the world’, being particularly struck by the archival research on the ping-pong between the Bank of England and UK Treasury officials over the potential risks of allowing financial ‘wizards’ to set up in UK territories and feed global money into the City of London. I also wondered why there wasn’t more academic research of that sort – there is, for example, on monetary policymaking, so why not on financial regulation?

The answer, as so often, is just my ignorance.

Catherine Schenk (professor of economic history at Glasgow) has been doing just this for some time. ‘Summer in the city: Banking failures of 1974 and the development of international banking supervision’, reconstructs the discussions around the creation of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and efforts to learn the lessons of crisis – lessons that would be repeated periodically, up to 2008 at least. The paper tells the story of the UK’s banking liberalisation and subsequent property boom of the early 1970s, followed by a sharp reversal that left many banks over-exposed. At the same time, the rapid internationalisation of banking, and growth of offshore centres since the late 1950s, was revealed to be well ahead of national regulators.

Catherine Schenk (professor of economic history at Glasgow) has been doing just this for some time. ‘Summer in the city: Banking failures of 1974 and the development of international banking supervision’, reconstructs the discussions around the creation of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and efforts to learn the lessons of crisis – lessons that would be repeated periodically, up to 2008 at least. The paper tells the story of the UK’s banking liberalisation and subsequent property boom of the early 1970s, followed by a sharp reversal that left many banks over-exposed. At the same time, the rapid internationalisation of banking, and growth of offshore centres since the late 1950s, was revealed to be well ahead of national regulators.

Schenk’s story features frauds and fragility from St Helier to Tortola… and, in 1975, the creation of the Basel Committee.

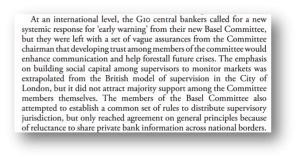

An important consideration for the Committee was the gap between “home” and “host” country regulators. (So, for example, a U.S. bank operating an entity in London would have the US as its home regulator, and the UK as its host regulator; the problem Schenk touches on is: who gets to regulate that London entity?) This home/host problem had also been a crucial one for the Basel Committee’s predecessor, the Groupe de Contact – and remained unsolved. Demands for an early warning system went unmet, in the face of different regulatory approaches and a common resistance to cross-border sharing of banks’ information.

The historic parallel with the 2008 crisis (and many in developing countries) doesn’t need much elaboration – primarily the use of less regulated jurisdictions to facilitate massive credit creation, feeding into property and other asset bubbles rather than productive investment. (TJN has written quite a lot about this, here.)

Sadly, the same underlying argument as in 1975 continues to prevent more effective regulation today: namely, that banks must trust their regulators enough to provide them with the sensitive information necessary for effective regulation — but this is incompatible with regulators sharing that information. Organisations as diverse as the Economic Commission for Africa and ONE have called for the Bank for International Settlements to publish their data on bilateral banking holdings; but that old argument about regulator trust keeps it private.

Is each crisis an opportunity? We’ve had a lot of similar crises, and missed a lot of opportunities to reduce the probability of repeat. This paper does a great job of exploring one of the big ones.

Endpiece

A new report to mention, and a call for papers.

First, in case you missed it, UNCTAD have released a major study on the tax implications of MNEs’ activity in developing countries – including an estimate of scale of $100 billion in lost revenues each year, of the same order as previous NGO estimates (albeit derived quite differently.) While that got the headlines, probably more important as research advances are the underlying analyses of MNEs’ tax contribution, and of the tax-depressing effect of their investing via offshore conduits. Roll on the World Investment Report 2015 in June, which will take this further. And kudos to UNCTAD for their valuable work.

The call for papers comes from UNU-WIDER, whose members are stepping up their interest in tax. The call is open until 30 April, and is part of WIDER’s new project on ‘The economics and politics of taxation and social protection’ which is also worth a look (includes call for research proposals and researcher vacancies).

As ever, ideas and suggestions for the Bulletin are most welcome – including music.

Related articles

The fiscal social contract and the human rights economy

29 April 2024

Ireland (again) in crosshairs of UN rights body

Inequality Inc.: How the war on tax fuels inequality and what we can do about it

New Tax Justice Network podcast website launched!

People power: the Tax Justice Network January 2024 podcast, the Taxcast

As a former schoolteacher, our students need us to fight for tax justice

Submission to the UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights’ call for input: “Eradicating poverty in a post-growth context: preparing for the next Development Goals”

17 January 2024

Submission to the Committee on Economic, Social Cultural Rights on the Fourth periodic report of the Republic of Ireland

The Corruption Diaries: our new weekly podcast