Alex Cobham ■ A Pyrrhic victory for the OECD?

The OECD secretariat has announced that it obtained agreement from the Inclusive Framework to press ahead with its own proposals, following US-French agreement of sorts – but at what price for the organisation’s legitimacy, and the future of international tax rules? I’ll discuss three scenarios, the implications of the announcement and the broader context. If you just want to read about the scenarios, skip to the bottom of this blog.

While the outcome is disappointing, it is of course not entirely surprising. The ‘Inclusive Framework’ is built on the OECD’s pledge that members would have an equal say – but even membership is premised on non-OECD countries that had no say in the first Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) process, in 2013-2015, having been forced to accept and implement the BEPS outcomes. It cannot be shocking, then, to see the OECD secretariat’s ‘unified proposal’ now confirmed in place of the work programme agreed by the Inclusive Framework last year. But a range of implications flow from this, and they are largely not positive for the OECD – although they may, eventually, set the stage for more positive global tax outcomes.

Immediate implications for the OECD process

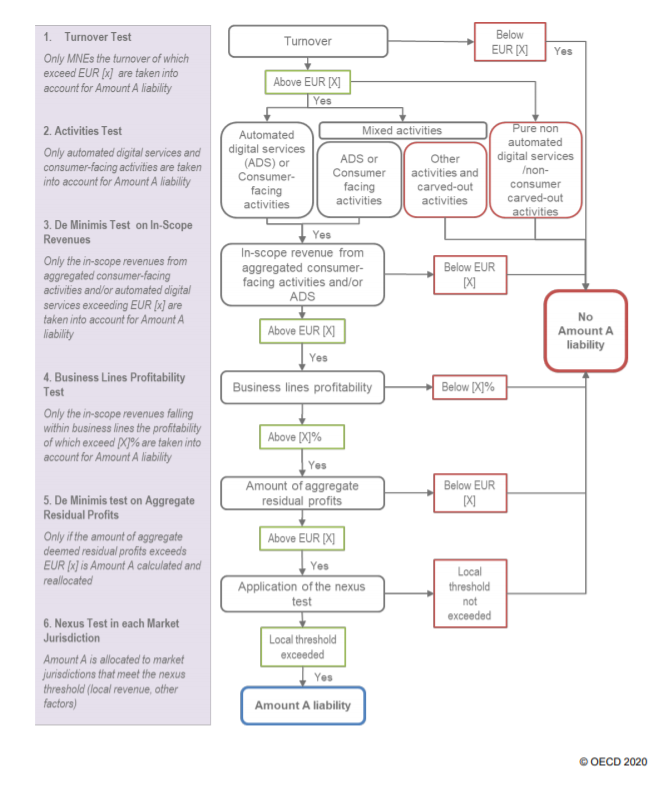

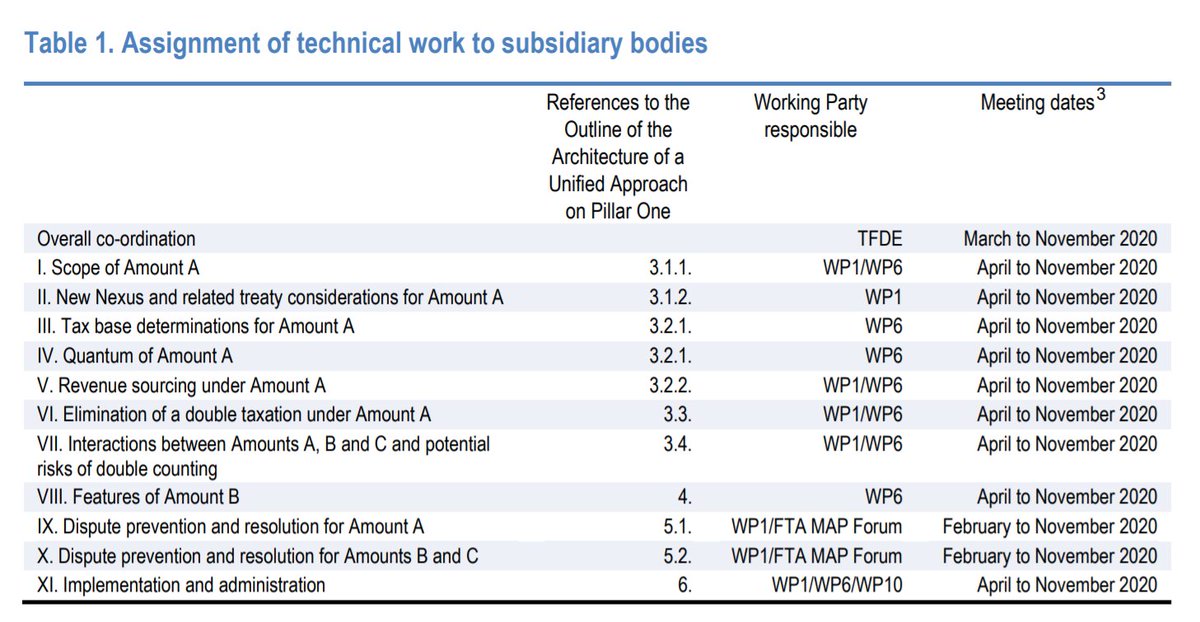

In terms of the OECD process, there is an insistence that things stay on schedule – that is, that everything must be wrapped up by end-2020. But there are so many, quite large things still open in Pillar One, from the scope of industries to be covered to the range of financial thresholds.

The 11 elements of work remaining on pillar one demonstrate how much is still open, even after the Inclusive Framework has been forced to drop its own work programme.

Even now, the work plan remains extremely ambitious. Taking into account that the public consultation saw strong and widespread objections on everything from the scope of Pillar One, to thresholds, to concept of dispute resolution mechanisms, only further brute force will obtain a 2020 conclusion.

One implication of these interacting pressures seems likely to be a tendency towards the lowest common denominator: that is, the need for quick agreement across a whole range of issues will set a tendency towards narrower scope, higher thresholds and less substantial redistribution.

And this is without mentioning that the US proposal for ‘safe harbours’ (or opt-outs for multinationals, if you prefer) is still noted in the OECD document. Unless the agreement was to note it and then never mention it again, that might well threaten the process down the track. There has been no suggestion that the US is ready to drop the idea, despite widespread opposition from other OECD members.

On Pillar Two, things remain very wide open – there’s not much new detail in the document, just an indication that work continues. One very welcome element: “Working Party 11 has set up a special subgroup on financial accounts.” An important technical issue that has come up in the process is the weakness of international accounting standards, or more specifically their failure to provide a common basis for any kind of unitary tax approach. It is fundamental for progress and any hope of certainty for tax authorities and taxpayers, that the negotiations can reach a common position on the data that will be relied upon.

Broader context

Stepping back, the broader implications of the politics seem larger than the technical challenges that remain. A quick look at the timeline:

- 2018: Comprehensive recognition, including from the OECD and with US support, that global reforms are needed and – crucially – that they must ‘go beyond the arm’s length principle’. This is a truly momentous shift, finally agreeing to unpick the League of Nations decisions of 1920s and 1930s that imposed the separate entity approach and with it the path to increasingly unsustainable transfer pricing approaches as multinational companies became increasingly global, complex and structured to avoid. The framing, in a commitment to a fairer distribution of global taxing rights, is equally significant.

- January 2019: The Inclusive Framework agrees a work programme with three proposals on Pillar One, including the G24 proposal for a relatively full unitary approach with formulary apportionment. All three proposals include a unitary approach; the big question is what element of transfer pricing may remain in place, if any.

- Summer 2019: A deal between the US and France, subsequently backed by the G7 group of countries, becomes the basis on which OECD secretariat brings forward its own ‘unified proposal’. This eliminates the G24 approach and the rest of the Inclusive Framework’s agreed work programme, and replaces it with much more complex and uncertain arrangements, per the US-French position. The main attraction appears to be that the various issues of scope and amounts A, B and C offer the possibility of introducing a unitary element but without any significant shift in taxing rights – either away from the main corporate tax havens, nor towards the lower-income countries that lose the greatest share of revenues to avoidance, but still increasing revenues for OECD members.

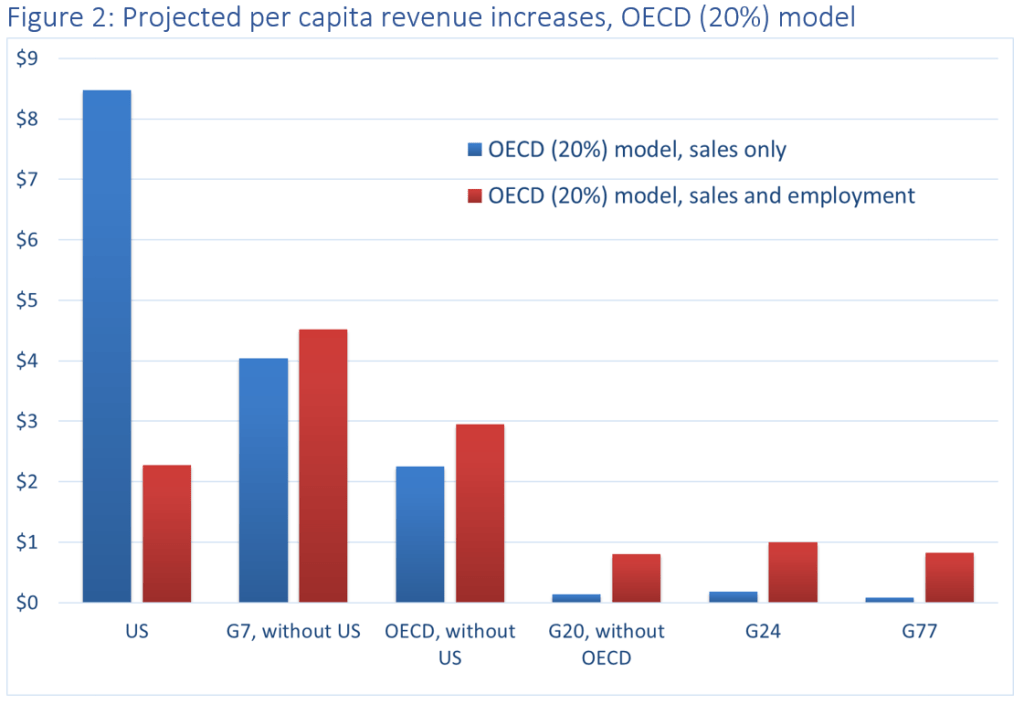

- Autumn 2019: The subsequent public consultation and private responses, not least from G24 members, show widespread discontent with both the secretariat proposal itself, and the undermining of the agreed process. The failure ever to evaluate the Inclusive Framework work programme’s three proposals is a particular issue. For that reason, there is great interest and concern about our analysis, commissioned by ICRICT, that uses the only public data (on US multinationals) to show the potential implications of the new proposal. In our figure 2, we model a heavily simplified version of the OECD proposal (the blue bars) – and the implications are clear, with global inequalities in taxing rights actually exacerbated rather than ameliorated as once promised.

Finally, as we have seen, the US went back on the deal with France, and December 2019 and January 2020 have been spent in their public and private dispute and renegotiation, concluding only as the Inclusive Framework meeting begins.

Political implications

And now the Inclusive Framework has ‘agreed’ to go ahead with the secretariat’s ‘unified proposal’, tweaked for the US-French position which remains without full agreement, but with the continuing commitment to urgent finalisation within 2020. What does this mean for the current reform process, and the longer-term dynamics? There are two main aspects.

First, for the current reforms, there is a real risk. Most of the ambition, in terms of redistributing revenues away from tax havens, has already been sacrificed in the unified proposal – which brings complexity without benefits, especially for lower-income countries. But that weak and complex outcome may still come with a high cost – because the spectre remains of mandatory binding dispute resolution, which would tie the hands of lower-income countries in particular in the face of multinationals’ aggression.

At the same time, any promised benefits of Pillar Two remain at best uncertain – and quite possibly entirely ephemeral, if a global blending approach were to be demanded by the US and others.

Second, however, it is the broader political ramifications that may prove to be the most important. The questionable credibility of the ‘Inclusive Framework’ is in tatters. As the Indian delegate said last year, ‘just because you call something ‘Inclusive’, does not make it inclusive’.

The Inclusive Framework’s agreed work programme has been thrown out, in favour of a secretariat proposal designed purely to meet the demands of two big OECD countries, the US and France (the biggest member and the OECD’s host country). The OECD’s claims that Inclusive Framework members have an ‘equal say’ have been shown to be completely hollow. The complete elimination of the G24 proposal in particular, and the Inclusive Framework’s forced acceptance of the unified proposal this week, has confirmed lower-income countries’ irrelevance at the OECD.

It’s hard to see how any future OECD process can make any credible claim to be inclusive. A good many OECD members may feel excluded; while the remaining Inclusive Framework members probably feel that their presence has done nothing but allow the OECD to bolster its claims to legitimacy.

Listening in the morning’s press conference to Pascal Saint-Amans talk about the importance of this agreement to avoid a (US-France, or global) trade war, you can only feel sympathetic. Within the problems facing the secretariat was a tradeoff between being vaguely inclusive, or addressing this threat. But that dynamic will always exist at the OECD, and so claims of inclusivity of non-members will never ring true. The comprehensive demonstration this week that the Inclusive Framework can simply be bent to OECD members’ perceived priorities has surely removed any last doubts.

Where next? Scenarios and opportunities

A major question now is where the next global tax talks after 2020 will take place. Such talks will certainly be needed, even if the timetable for BEPS 2.0 can be kept, and the OECD seems unlikely to be able to claim ‘inclusivity’. In the absence of new talks, and perhaps also in their presence, an explosion of unilateral measures seems the most likely outcome.

Those countries pursuing DSTs (digital services taxes) seem at least to have obtained some of the Trump administration’s attention, and so far no punitive response – confirming the value at one level of unilateral actions.

At the same time, the continuing resistance of OECD members to any meaningful UN process on international tax rules seems unlikely to dissipate any time soon. As the high-level participants at our virtual conference in December concluded, things will not be fixed by this OECD process – but ‘the genie is out of the bottle‘ as far as unitary taxation is concerned.

We had earlier identified three scenarios for the OECD process:

- Limited reform. In this scenario, intended to meet US demands, the secretariat would deliver a reform that would redistribute little profit from tax havens, with some revenue benefit for major OECD countries and little for anyone else.

- Process collapses due to lack of trust. In this scenario, the refusal to allow G24 countries or others the ‘equal say’ promised to the Inclusive Framework would be met by a rejection of the secretariat, and ultimately a collapse of the process.

- Reset. Here, the threat of collapse would see the secretariat forced to make concessions to the Inclusive Framework. This would necessarily include a longer timeline, recognising that 2020 is simply too short for such a major overhaul of the rules, and an agreement to evaluate fully the three proposals that the Inclusive Framework had agreed to consider, including that of the G24.

As things stand, the secretariat has avoided scenarios 2 and 3 for now. The Inclusive Framework has been forced to accept the path to limited reforms on the basis of US-French dominance. Scenario 1, an agreement of sorts by end-2020 is now more likely; but it is also certain not to be the last word.

The Inclusive Framework has, perhaps, one last chance to bring concerted pressure to bear by June 2020. It’s conceivable that the G24 could demand a reopening of the issues and also the timeline, so that there could actually be an evaluation of the revenue implications of different proposals. A public demonstration of discontent might be worthwhile, despite the likely rebuff.

The chances are, in either case, that there will be no reset, and therefore no prospect in this process of considering the more full unitary approaches that would deliver meaningful redistribution of taxing rights, as was the initial promise of the negotiations. But that does not make this a success for those who favour minimal change from the status quo: the more complex and limited the outcomes of the OECD process, and the greater the insistence of the multinationals on binding dispute resolution, the greater the chance that this proves to be, for the OECD and its main members, a truly Pyrrhic victory: a deal that creates great uncertainty itself, and is followed immediately by multiple unilateral measures.

The OECD should be congratulated for holding things together this week; but the longer-term implications seem likely to be substantially damaging for international tax coordination, and for the organisation’s credibility as a broker of reforms.

Meanwhile, a number of G24 countries and others will currently be discussing their next moves – and it seems inevitable that much of their analysis will focus on options outside of the OECD and the Inclusive Framework. The Tax Justice Network, and the broader tax justice movement, will be active in supporting technical and political discussions alike. The upcoming Bangkok conference of the Financial Transparency Coalition can provide an important moment for broader evaluation.

Over the next year, the recently announced UN high-level panel on financial accountability, transparency and integrity (FACTI) will work to identify key priorities to address gaps in the international architecture that impede progress against illicit financial flows – including the major component which stems from the tax abuses of multinational companies. With power dynamics at the OECD laid bare this week, FACTI has a clear opportunity to propose a UN tax convention that would lead to a new, and globally representative forum for future policy negotiations.

Related articles

🔴Live: UN tax negotiations – First Session

What to know and expect ahead of this week’s UN tax negotiations

Ireland (again) in crosshairs of UN rights body

Proposal for ‘Business in Europe: Framework for Income Taxation’ (BEFIT): A wrong turn in the right direction

2 February 2024

Formulary apportionment in BEFIT: A path to fair corporate taxation

31 January 2024

New Tax Justice Network podcast website launched!

El secreto fiscal…tiene cara de mujer: January 2024 Spanish language tax justice podcast, Justicia ImPositiva

Tax Justice Network Arabic podcast #73: ملخص 2023

The UN Tax Committee spreads its wings