Alex Cobham ■ Advance tax rulings: Publish or abolish?

Advance(d) tax rulings give multinationals a degree of certainty – but at what cost to tax justice?

A range of cases, largely based on leaked documents rather than public disclosures, reveal two major issues: large revenue losses, and a clear risk of corruption. Would mandatory publication be sufficient to curtail these risks? Or is the entire approach so open to abuse that it would be better to abolish advance rulings entirely?

Advance tax rulings, including Advance Pricing Agreements (APAs) and Advance Thin Capitalisation Agreements (ATCAs), aim to give multinational companies a degree of certainty about some elements of their tax treatment, although the research literature is somewhat mixed on this point. [Note that this post deals specifically with unilateral rulings; by and large the risks should be much smaller when negotiated with two or more jurisdictions. For more on this point, see the Financial Secrecy Index indicator on corporate disclosure.]

One study found that unilateral tax rulings were under-used, given the evidence on the existence of uncertainty. But others highlight an incongruence between the theory and practice, as usage became increasingly widespread. More complex modelling suggests that multinationals facing high uncertainty will not necessarily seek rulings when tax authorities use them carefully to limit their own audit costs, and to gather information to allow them to identify specific revenue risks.

Advance rulings may at least allow tax authorities to focus their limited resources elsewhere. But not without risk. For one thing, the negotiation over advance tax rulings may be even more unbalanced than the usual negotiation over multinationals’ actual tax payments. The tax authority has no threat of demanding audit or payment; and cannot devote the same level of resources.

Secrecy and corruption risk

A bigger risk, perhaps, is that advance tax rulings are typically secret. This opens up two particular issues.

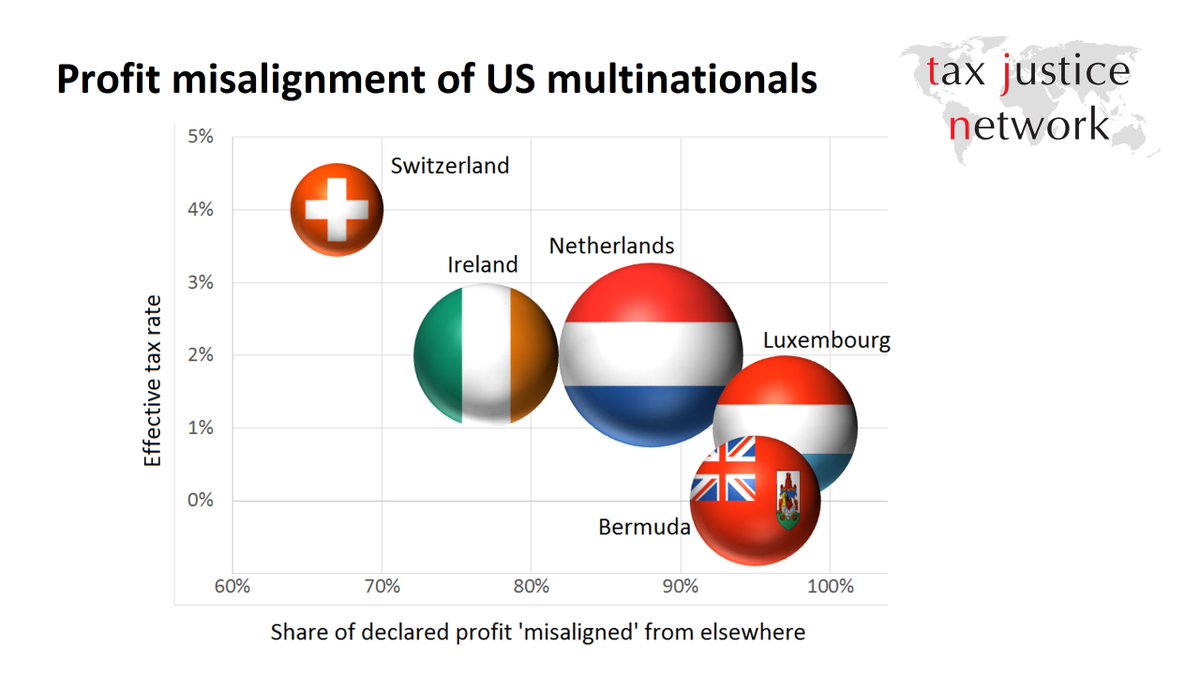

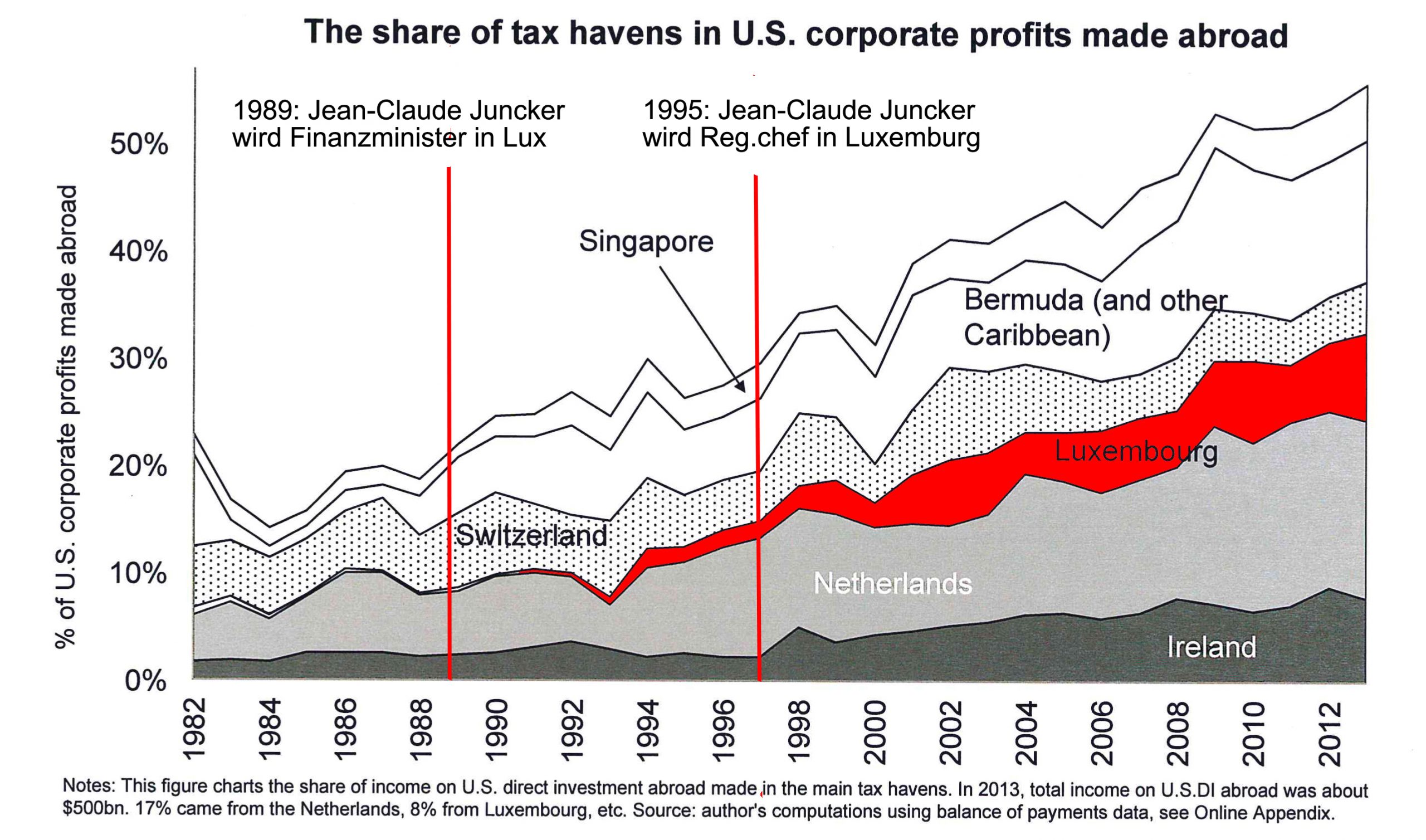

First, consider the case where a country is set on attracting profit shifting – that is, on encouraging tax avoidance to the detriment of the jurisdictions where the profits of their ‘client’ multinationals actually arise. The corporate ‘tax haven’ (say Ireland, Luxembourg or Netherlands) may have a perfectly respectable tax system on paper, meeting various international standards – but in practice, still use these secret deals to provide multinationals with special treatment.

This confirms the need for public scrutiny of advance pricing and advance thin capitalisation agreements. These dull titles hide the fact that they are contracts with private companies that reallocate significant public resources. Given the potential to create quite extraordinary private gains, as appears to be the case with F1, there can be no justification for their ongoing secrecy.”

For another example of the ongoing abuse of secrecy around these rulings, we can turn to the Netherlands – and further impacts of leaks, in this case the Paradise Papers. One revelation among many in the files of the offshore law firm Appleby was an advance ruling enjoyed by Procter & Gamble. This prompted an immediate review in late 2017 of around 4,000 rulings by the Dutch government. At the time, Finance Minister Menno Snel indicated that the problem was just one of procedure, telling parliament: “We don’t have any clues that it is a wrong ruling in itself.”

That same minister has now reported that 78 rulings were made improperly, often signed off by a single local inspector rather than the advance rulings team, in a detailed report to parliament. Bear in mind that the Procter & Gamble ruling is described as saving $169m in tax in Netherlands, with $676m moved untaxed to Cayman. Signed off by a single, local tax inspector, with apparently no oversight of any sort.

Imagine that happening in the context of a lower-income country: $676m in tax base given up, in secret, by a single civil servant. And perhaps 78 times as much… But somehow we don’t think it’s a corruption risk because we’re talking about the Netherlands rather than, say, Nigeria? (That’s another point – but we really do need to interrogate the biases that underpin our perceptions of corruption.)

The scale of the problem

The Finance Minister’s report – and its five appendices – appear to studiously avoid any assessment of the overall revenue implications. The back of the envelope picture should worry us though. The Procter & Gamble ruling that began the probe just happened to be in the Appleby leak, so let’s take it for a moment as randomly selected and make the heroic assumption that it is broadly representative. A back of the envelope calculation gives a potential $52 billion in shifted profit, effectively saving $13bn in Dutch tax.

Finance Minister Snel defended the value of advance rulings, but also raised the possibility of denying them to companies with no real substance in the Netherlands:

Prior consultation and giving certainty in advance are core elements in the supervision of the tax authorities and are an important pillar of our business climate. The question is, given the Cabinet’s intention in the coalition agreement to counter letter box constructions, or whether certainty needs to be given in advance to companies that make a limited contribution to the real economy.”

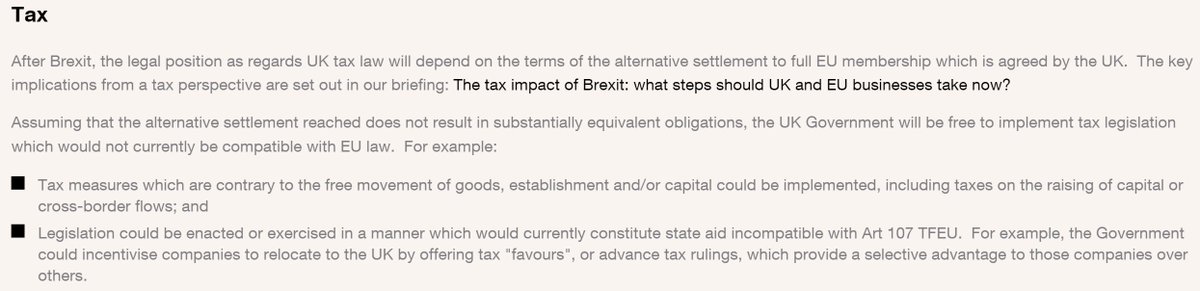

The European Commission’s state aid investigations also continue to put pressure on EU members that have used bespoke deals to undermine each others’ tax bases. And so the opportunity to attract a boatload of profit shifting from neighbouring countries, and then tax it at a near-zero rate, has not passed the Brexit lobbyists in the UK by…

Here’s law firm Clifford Chance describing what the UK government would be ‘free’ to do:

{Clifford Chance’s Dan Neidle points out on twitter that this would in fact only apply in a ‘hard’ Brexit, where there were no provisions equivalent to the state aid rules.}

{Update: Dan has now updated the Clifford Chance briefing to reflect this point, and to take a more neutral stance on the policy options open to the UK government post-Brexit.}

Abolish or publish?

Advance tax rulings clearly offer greater scope for multinationals to achieve tax reductions, than the much-discussed tax ‘certainty’. Certainty, after all, could be largely achieved by not taking on any risky positions – and yet all(?) multinationals deliberately choose risky tax positions.

Our senior adviser David Quentin has modelled this process of risk-taking, demonstrating how it allows multinationals with their tax advisers to load the costs onto the public purse. And sadly there’s plenty of evidence on the real risk appetite. Five years ago, the UK Parliament’s Public Accounts Committee savaged the big four accounting firms after uncovering documents that showed their willingness to market tax avoidance schemes with only a 50% chance of succeeding in law should they be challenged.

And just last week, this was brought up to the present day by the B Team – in theory, leaders in corporate social responsibility – when they published their new ‘responsible tax’ principles. The second of their seven principles is headed ‘Compliance’, and here the group identifies the appropriate standard of responsible behaviour as follows:

We aim for certainty on tax positions, but where tax law is unclear or subject to interpretation, we evaluate the likelihood and where appropriate seek an external opinion, to ensure that our position would, more likely than not, be upheld

More likely than not, i.e. over 50%… So the aim is certainty, but the willingness to tolerate uncertainty if there is a tax saving is in fact very high. If advance rulings offer certainty, and the B Team stance is representative, it would explain the research finding that firms with tax rulings have lower effective tax rates. (NB. This research relates to LuxLeaks and would of course be greatly enhanced if all rulings were made public, so that the sample could be extended.)

In these circumstances, what if any are the benefits to tax authorities or to citizens from allowing advanced price rulings? And if there are benefits, do any of these stem from the rulings being secret? Or is this is a one-way street, where the claimed priority of tax certainty for multinationals is actually used to construct a more unbalanced negotiation, with secrecy to cover any outcome however unreasonable – and at the same time, encouraging corrupt behaviour.

If certainty is the aim, it seems clear that secrecy should have no role to play. If demonstrating the fair tax treatment of all is a concern, then emphatically secrecy should have no role to play. And if resisting corruption matters, secrecy should have no role to play.

There is an ongoing debate about whether corporate tax returns in full should be made public – e.g. it was the topic of the last session of our annual conference in 2017. But whatever your view of that, it’s hard to see how anyone could defend the ongoing special treatment of multinationals through the secrecy, in particular, of advanced tax rulings.

We only heard about Procter & Gamble’s deal through the #ParadisePapers. We only heard about the systematic Luxembourg abuse of rulings through #LuxLeaks. Do we really want leaks to be the basis for the effectiveness of corporate taxation, or the accountability of multinationals and of tax authorities?

Example: My story on Day 1 of #Tax4Dev: Vodafone Expects CbC Reports to Be Public ($) https://t.co/DgNwcZbjgY

— Stephanie Johnston (@SoongJohnston) February 20, 2018

But secret advanced tax rulings would still incentivise systemic abuse and corruption, for which reason they are penalised in the Financial Secrecy Index. Give us transparency please, through open publication of all advance tax rulings in force – or abolish them, if it’s not possible to curtail the risks of revenue loss and corruption in this way.

Postscript: Some responses

1. Are advanced tax rulings just a mechanism to corrupt the normal application of tax rules to multinational companies? (A quick thread as work avoidance)

— Alex Cobham (@alexcobham) February 20, 2018

There were some great responses on #taxtwitter – here are just a few. In summary: lots of support for (redacted) disclosure; little or no defence of the current secrecy.

Rulings w/ proper redaction should be publicly disclosed. This not only allows sunshine to disinfect any abuses but also provides fairness to other businesses seeking rulings. Also secrecy creates privileged class of practitioners. “Secret law is an abomination.” – Kenneth Davis

— Martin Sullivan (@M_SullivanTax) February 20, 2018

Think it would be helpful to all for the parameters of rulings to be public (as is broadly the case in US). Fisc would not be asked as many questions; companies would have more certainty; trust would increase.

But need to address genuine confidentiality concerns eg in Pharma.

— Heather Self (@hselftax) February 20, 2018

Advance rulings (A) providing certainty are good (they reduce administrative and compliance costs) (B) providing substantive special tax relief (especially if they are pretending to be (A)) are bad (secret, non-neutral taxation). In either case, redacted disclosure seems right.

— Martin Sullivan (@M_SullivanTax) February 21, 2018

Great thread. Fortunately in India advance rulings are public. Points are valid for APAs, though. https://t.co/3UpL9JzR1z

— Surya Prakash B S (@SuryaPrakashBS) February 21, 2018

Aside from the transparency issue, the process of deciding/issuing rulings can be a problem, esp in weak capacity cases. Eg, MoF issues rulings, doesn’t inform Rev Auth and taxpayers pull them out whenever suits them in the tax compliance process

— Marijn Verhoeven (@MarijnVerhoeven) February 20, 2018

Excellent framing of important debate. Is there a blog where can write more detailed response than on twitter. My quick twitter reaction is “certainty is worthwhile” but must be tempered by no secrecy and ability to review later for more tax (but no penalty)

— David S. Lesperance (@dslesperance) February 20, 2018

1. rulings should not be wholly secret, redacted summaries of the decision and the technical basis should be made public as is the case in US and Aus. In effect secret rulings are unfair to taxpayers and deleterious to good administration of the tax system

— Patrick S Fitzgerald (@p_sfitz) February 20, 2018

Any democratic society is entitled to know how certain tax payers (multinationals) make use of their (tax) laws, how their tax administration deals with these tax payers and whether potential abuse is made of these laws.

— Adam (@Adam13576) February 20, 2018

Would also be good if you could mention the point that, at least in Europe, tax authorities are pushing businesses to resolve points of uncertainty up-front. Indeed a UK bank that did *not* seek a ruling would be breaching the banking code of practice.

— Dan Neidle (@DanNeidle) March 2, 2018

Related articles

The secrecy enablers strike back: weaponising privacy against transparency

Privacy-Washing & Beneficial Ownership Transparency

26 March 2024

Ireland (again) in crosshairs of UN rights body

Tax policy and gender disparity: A call to action on International Women’s Day 2024

Policy research conference: How a UN Tax Convention can address inequality in Europe and beyond

The IMF’s anti-money laundering strategy review is promising, but it all comes down to implementation

Inequality Inc.: How the war on tax fuels inequality and what we can do about it

Proposal for ‘Business in Europe: Framework for Income Taxation’ (BEFIT): A wrong turn in the right direction

2 February 2024

Formulary apportionment in BEFIT: A path to fair corporate taxation

31 January 2024

While I tend to focus on private client vs. corporate tax, I agree that the current non-transparent system is subject to real (or at least potential) abuse. This could result in direct corruption or the placement of too much decision making power in the hands of one tax official. There are some good points to be made regarding privacy (especially in pharma) but at most that might call for redacting as opposed to continuing non-publc disclosure.

While country by country reporting may be a “perfect”solution, seeking it should not stand in the way of a doable “good” solution of global adoption of the standard of redacted publication of tax rulings and committee approval standards.